This October, we organised a panel discussion about “Who will influence the success of preprints in biology and to what end?” at FORCE2019, the annual conference for the FORCE11 community. We continued discussions over dinner after the panel session (read our report here).

The landscape of preprints in biology and chemistry is changing rapidly: at least eight new preprint servers have launched in the past year alone, established by journals, publishing vendors, scientific societies and research communities. Moreover, several publishers now permit or even promote preprints, some (such as PLOS) by facilitating posting to bioRxiv, others (such as the BMC journals) by running their own services. The significant and continued growth in preprinting at bioRxiv as well as the initiation of numerous other preprint-related initiatives in recent years may be evidence enough that the principle of preprints has been proven.

However, the conceptual vision for preprints in the life sciences – and current progress toward this vision – varies depending on who you ask. For example, preprint server operators, journal publishers, preprint authors and readers, funders, policymakers and advocates may all have different normative ideals concerning:

- What material should be preprinted?

- When should preprints be preprinted, relative to formal publication?

- What kind of feedback should be collected on preprints and how might authors respond?

- How and by whom should preprints be filtered and curated, and might this create reputational indicators that feed into research evaluation mechanisms?

- How should preprints be reused?

Additionally, the future of preprints is uncertain. The rate of growth in preprint submissions is higher than that of publications, yet only 1 in 50 biomedical publications is preprinted today and uptake varies across research communities: for example, a third of recent submissions to bioRxiv are from only 3 of the 27 research categories on the platform: neuroscience, bioinformatics and microbiology (from https://rxivist.org/stats). While one funder (the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, CZI) mandates preprints, there is a call for more funders to follow suit (Plan U). Meanwhile, the advocacy and adoption conversations we have and hear about at Accelerating Science and Publication in Biology (ASAPbio) remain dominated by fears relating to research evaluation and misuse: fears of scooping (including the perception of someone else unfairly gaining from your work), journal rejection, and the repercussions of finding errors in one’s own work and sharing erroneous science by others. These fears were also identified as dominant in a recent study on the current perceptions of preprints in biology, which also highlighted the importance of Twitter in the dissemination and visibility of preprints.

At this point, it is important to reflect together critically on:

- What would successful adoption of preprints in biology look like to you?

- What do current preprinting practices (the who, how, where, when and why of posting and interacting with preprints) tell us about progress towards this vision for success, and the drivers and blockers influencing adoption?

- Who makes the decisions about how preprinting is delivered, technically and socially?

- For whom do preprints not automatically work? For whom and by whom are they built, and who is not included?

- What are some possible unintended consequences of these decisions and is anyone mitigating these?

- What may threaten the success of preprints in biology?

And so we invited discussions on “Who will influence the success of preprints in biology and to what end?” at FORCE2019, the annual scholarly communications conference for scholars, publishers, technologists, librarians, funders and others interested in improving scholarly communication “through the effective use of information technology”.

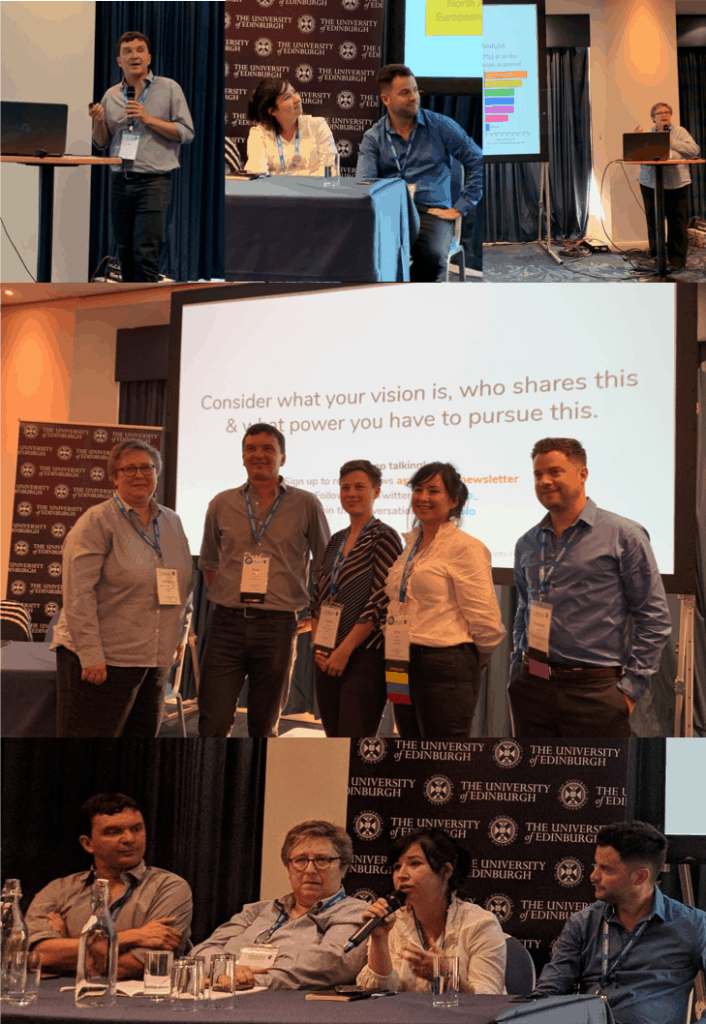

The above question was addressed during a panel discussion on Wednesday October 16 between:

- Theodora Bloom, executive editor of the BMJ and co-founder of MedRxiv

- Humberto Debat, researcher at the National Institute of Agricultural Technology, Argentina

- Amye Kenall, editorial director for medicine and life sciences journals at SpringerNature

- Dario Taraborelli, science program officer at CZI

- Naomi Penfold (moderator), associate director at ASAPbio

Naomi introduced preprints as one way to improve transparency and speed in the process of communicating science, by sharing the input (manuscript) and process (peer feedback and review) as well as the output (journal article). While preprints could bring collective benefit by advancing science, adoption in biology right now is driven by incentives and concerns relevant to the individual researcher. With journals, funders and researcher advocates all playing a role, she asked the panellists “What is your vision for success for preprints in biology? Who will drive this success?”

Dario started with a vision for “preprints as a live object” — a staging area for science that can advance more open and collaborative model for science, beyond publishing as we know it today. He highlighted CZI’s multi-pronged approach to supporting preprints: with funding, technology, policy and user research. For example, in Meta, CZI’s research discovery tool, preprints are treated as first-class research outputs equal to other objects.

While preprints could bring more fundamental change to science communication in the future, as Dario envisions, Theo and Amye both argued that the traction of preprints in biology so far has been due to keeping the process simple and easy for authors. By sharing the existing manuscript online before peer review, preprints are a one-step change for authors with benefits in line with the authors’ own interests. Theo listed many reasons why people post preprints to bioRxiv (as reported in a recent survey by the platform), and noted that for clinical sciences, there are additional risks to mitigate, namely the risk of “sharing incorrect information or conclusions that could harm individual or population health”. At medRxiv – a preprint server for the clinical sciences launched in June this year by BMJ, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and Yale – a lot of care and attention is being put into screening submissions before posting any preprint online. A fifth of medRxiv submissions are escalated for discussion after screening, and the screening team always ask: “is there a benefit in sharing this before peer review?”. While the proportion of submissions that are not posted is higher at medRxiv than for bioRxiv, the majority are posted. Theo argued that having clinical experts and experienced editors behind medRxiv has been essential in building trust, and she raised the question of whether it matters how platforms that host preprints are run and whether these differences should be more transparent.

The impact of making it easy for authors may be reflected by the relatively high opt-in rate (35% manuscripts) that Amye reported for BMC’s In Review service, where authors are able to agree to the manuscript being posted online (without any additional work by them) once it has passed initial triage and is undergoing peer review at the BMC journal they submitted to. Amye shared that “89% of authors say it improved their publication experience”1.

One benefit of sharing before peer review is to catch errors faster, and allow time for the community to improve the manuscript before it is released as a final version of record, the potential benefit of which Amye illustrated with a recent case where a reader spotted an error a day after a journal article was published leading to retraction of the article. With preprints, this kind of feedback can be provided before the manuscript becomes a version-of-record article, reducing the chance that misleading or inaccurate information is shared more widely.

The importance of compelling incentives for authors to post their work as preprints was reiterated by Humberto, who painted a holistic picture of life as a researcher in Argentina: with relatively low income and research output compared to other countries, researchers in Argentina are posting 6.5% of their publications in the life sciences as preprints (more than the overall average of 3%). He reported that both dissemination and visibility of their research for no cost are key attractive features of preprints.

After the panellists’ points, the whole-room discussion included questions and points about best practices, licensing, equity and sustainability of preprint servers. The introduction of best practices for preprint servers was suggested2 while the topic of licensing for preprints was discussed: does a preprint server limit the licensing choice to CC-BY (the license of preference for open access) or provide authors with a choice of licenses, given the author many not know the full consequences of their licensing choices? Also asked: who do preprints not work for, and who will pay to sustain preprinted content in 10 years’ time? In their closing statements, the panellists reflected on all they’d heard: Dario and Theo asked how to make preprints more inclusive and equitable, for example by being more flexible about the language requirements for preprints (bioRxiv and medRxiv require preprints to be written in English), while Amye advocated for standardising key elements of quality control for preprints, and Humberto reminded us that preprints are an opportunity to bring about radical improvements to science.

The panel discussion illustrated that publishers, technologists and researchers bring their own experience and perspectives to how they envision success of preprints for biology, and who will drive that success. While publishers recognise the practical importance of keeping any process simple, easy and as minimal burden as possible on authors, innovators and early adopters hope for bigger changes in the name of improving science at large. The current adoption of preprinting is being driven by the way preprinting is made possible by service providers and how authors are responding, based on their needs, wants and understanding of the complexities surrounding preprints. Several questions remain: beyond the preprint author, how might the needs of the reader be better supported? How might the rate of preprinting change in different communities, and why? And will the more radical visions of preprints changing how science and scholarship is done come true?

The panel presentation slides are available from Zenodo. This blogpost builds on the abstract for the panel discussion, also available from Sched. The panel session was live-tweeted by Emmy Tsang (first tweet; threadreader).

Footnotes:

- From a survey of authors using BMC In Review (not published). In comparison, some publishers facilitate posting direct to bioRxiv upon manuscript submission (and before the decision to send to review or not). As an example, PLOS has reported that the opt-in rate for posting submissions to bioRxiv varies with the location of the corresponding author’s institution, with the highest opt-in rate being 33% for work from Ugandan institutions.

- Maria Levchenko illustrated the reasons behind her call for community best practices for preprint servers in her poster for the FORCE2019 conference.

3 Comments