Humberto Debat1 & Richard Abdill2

1 National Institute of Agricultural Technology (IPAVE-CIAP-INTA), Córdoba, Argentina; 0000-0003-3056-3739; @humbertodebat

2 University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States; 0000-0001-9565-5832; @richabdill

The majority of scholarly work in biology is published in English, a language most of the world does not speak. To help remediate this key issue hindering inclusive scientific dialogue, we built PanLingua, a multilingual preprint search tool intended to enable search and global access to machine translations of all preprints hosted by bioRxiv.org: users can enter search terms in their native language and view search results linking to the full text of all available manuscripts, translated into more than 100 languages. The tool is open source, and we welcome feedback from users about how you’re using the tool or how it could be improved.

Over the last five years, researchers in the life sciences have embraced preprints like never before, sharing their results online before publication in conventional journals. The wide majority of these manuscripts now appear on bioRxiv, where one of the only requirements for acceptance is that all manuscripts must be written in English, a criterion shared by most of the world’s largest and most popular scientific journals. So while there is much discussion about broadening access to scientific literature, the debate is essentially about access to English-language scientific literature, an omission that obfuscates a key obstacle to those seeking the knowledge available within scholarly articles.

There is much work needed to balance the asymmetries of scientific discourse, which currently flows mostly from the North to the Global South. Automatic translation platforms have greatly improved their efficacy in the last few years and represent a valuable opportunity for readers to grasp the essence of a text written in a language they may not speak, as observed last year by Daniel Prieto, our colleague from Uruguay, in his call for the scientific community “to develop a comprehensive multi-language translation tool with the help of services such as Google Translate… [to] enable international researchers to access regional databases not compiled in English.”

Google Translate is already capable of providing passable translations of individual articles, but readers do not have a convenient way to search the vast collection of scholarly outputs in other languages. This is the modest improvement offered by PanLingua in the broader challenge of reducing language barriers in scientific dialogue. We encourage others to develop similar tools — not only to broaden access to English-language scientific works, but also the evident counter-platform, which would help English speakers search the millions of non-English scientific literature available — for instance, the 79 million articles published in Chinese, or the 1.5 million open-access works in Portuguese, Spanish, French and other languages available at LA Referencia.

How it works

In short, most of the work is done by Google and bioRxiv:

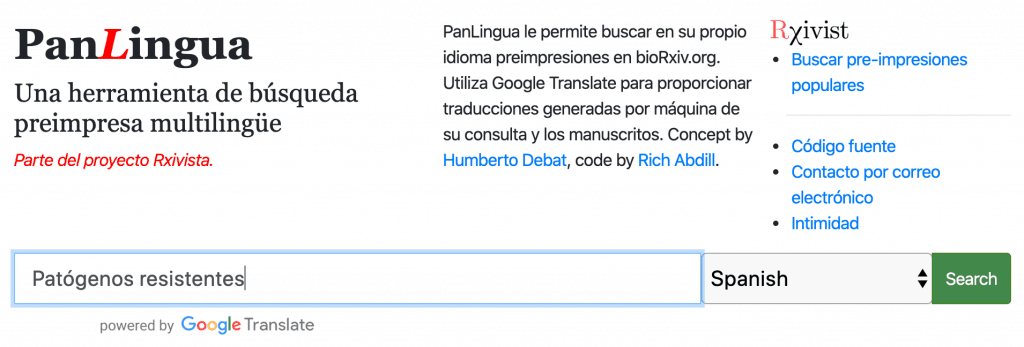

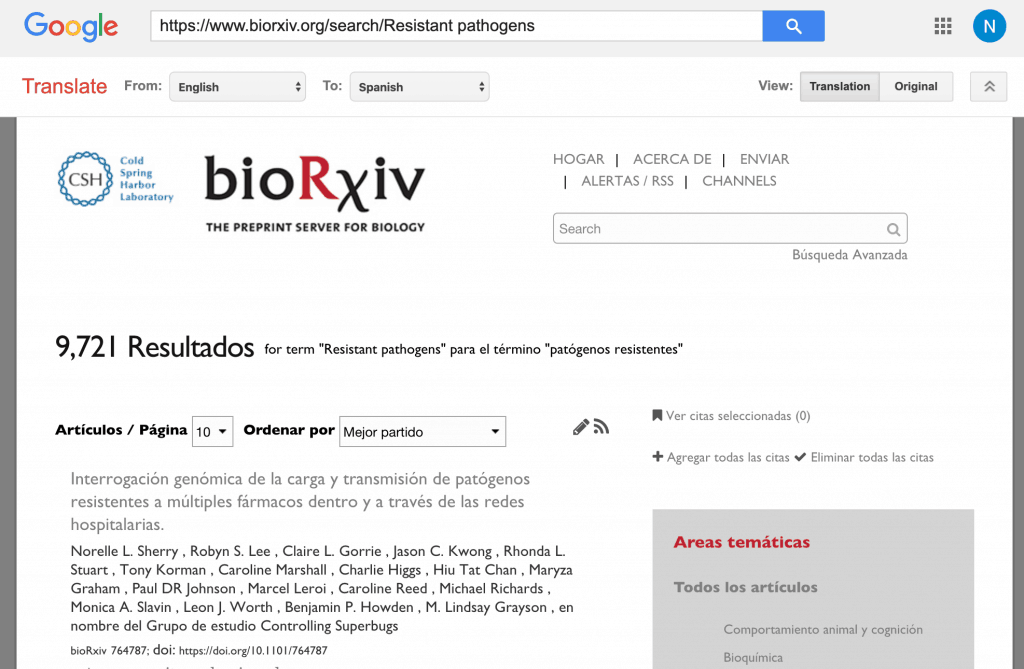

- A user arrives at panlingua.rxivist.org. They are presented with a search box and a list of languages supported by the Google Cloud Translate API.

- The user inputs a search term in their chosen language and submits the form.

- The user’s input is sent to the Google Cloud Translate API, which provides an English translation of the search term.

- The translated search term is used to generate a URL of the standard bioRxiv search.

- The generated bioRxiv URL is passed to translate.google.com, which provides a translated version of that page in whatever language was originally selected by the user.

- The user is redirected to the translate.google.com page with the search results.

- Links within the translated search results point to the translated versions of each paper, which means the user is now in an environment where full translated versions of the selected articles are available on their own language.

PanLingua owes its name to Xul Solar, an Argentine artist, writer, and inventor who described himself as “master of a script that nobody yet reads… creator of a universal language called Panlingua based on numbers and astrology that will help people know each other better.” While our tool does not take Xul’s route of enabling dialogue through a universal language, we believe available translation technology can serve as an effective intermediary to bond together the diversity of languages linked to scientific endeavor.

The use of machine translation in science is predicated on a straightforward notion: on the contrary to non-scientific literature, where translation is judged by aesthetics, the central goal of translated scientific literature is legibility. There are innumerable ways to translate a poem, for example: its richness goes beyond words and involves nuanced aesthetic resources requiring human discretion to interpolate. Scientific papers, on the other hand, can be comprehended with a much more literal translation — something machines can already do, at least for some of Google Translate’s 104 supported languages. “Close enough” is not ideal, and aspects of the original text can be lost, confounded, or tergiversated, but automatic translation at least allows users to arrive at the existence of the translated work and get a general idea of its content. Tools such as Google Translate are evolving at such speed that is not naïve to believe that they have grasped the threshold of basic legibility.

Science is a shared enterprise, a global endeavor enriched by a multiplicity of visions, realities and languages. Everyone benefits from the development of a more inclusive ecosystem, and seamless international scholarly discourse is a real possibility. Many barriers are stopping this utopia; let us remember language.

Find PanLingua at https://panlingua.rxivist.org/. The code for PanLingua is available from GitHub (https://github.com/blekhmanlab/panlingua) and archived on Zenodo, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3601512.

2 Comments