By Bodo M. Stern and Erin K. O’Shea

Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Chevy Chase, Maryland

Summary

Life scientists feel increasing pressure to publish in high-profile journals as they compete for jobs and funding. While academic institutions and funders are often complicit in equating journal placement with impact as they make hiring and funding decisions, we argue that one of the root causes of this practice is the very structure of scientific publishing. In particular, the tight and nontransparent link between peer review and a journal’s decision to publish a given article leaves this decision, and resulting journal-specific metrics like the impact factor, as the predominant indicators of quality and impact for the published scientific work. As a remedy, we propose several steps that would dissociate the appraisal of a paper’s quality and impact from the decision to publish it. First, publish peer reviews, whether anonymously or with attribution, to make the publishing process more transparent. Second, transfer the publishing decision from the editor to the author, removing the notion that publication itself is a quality-defining step. And third, attach robust post-publication evaluations to papers to create proxies for quality that are article-specific, that capture long-term impact, and that are more meaningful than current journal-based metrics. These proposed changes would replace publishing practices developed for the print era, when quality control and publication needed to be integrated, with digital-era practices whose goal is transparent, peer-mediated improvement and post-publication appraisal of scientific articles.

Introduction

Scientific publishing in the life sciences is going through a period of experimentation and questioning not seen since the appearance of open access in the early 2000s, when new online-only and open access journals challenged the traditional model of print distribution and subscription fees. More recent experiments in scientific publishing include preprints, open models of peer review, and micro-publications (the publication of smaller units, such as individual observations). Yet most scientific work in the life sciences is still disseminated following a process inaugurated by the Royal Society in the 17th century. This process (Fig. 1A) starts with authors submitting a manuscript to a journal of their choice, at which editorial selection and peer review culminate in an editorial thumbs-up/thumbs-down decision that determines whether the article is accepted for publication or rejected. If it is rejected, the author starts all over again at a different journal, typically until the paper gets accepted for publication somewhere. Subscription fees (in the form of single user licenses and institutional site licenses) and open access fees are the two prevailing payment options to compensate publishers for their services.

It made sense for publishers to charge consumers subscription fees in exchange for hard copies of journals and to establish editors as the gatekeepers of publishing, when printing and distributing scientific articles was expensive and logistically challenging. These limitations no longer apply. We propose here to reconsider hallmarks of this traditional publishing process – the subscription business model and the roles of journal editors, reviewers and authors – with the goal to better align scientific publishing with a digital environment and with a scientist-driven research workflow.

Open access: necessary but not sufficient

Advocates of open access have long noted problems with the subscription model, including the following:

- The academic research community, including research institutions and funders, consider their research output a public good. The subscription paywall constitutes a powerful conflict with their mission of sharing research data and tangible products openly and in a timely manner. Payment for research articles should therefore not come from consumers, since that limits opportunities to reproduce and build upon the research for future discoveries.

- The subscription price that publishers charge is inflated because it is not based on the specific value that publishers add. By imposing a toll for access to scientific articles that were created and evaluated by scientists for free, publishers hold these scientists’ products “for ransom,” charging for the whole product instead of for the publisher’s specific contributions to that product.

Future changes in scientific publishing should strive to ensure that research output is freely available from the time of publication (see https://oa2020.org/). Our arguments here extend beyond open access, however. While we consider open access necessary, it is not sufficient: an author’s payment for publication in the current open access model creates a strong incentive for publishers to accept papers independent of their quality, elevating the risk that publications become paid advertisements. The rise of so-called predatory open access journals, with fake editorial boards and fake peer review, is evidence that this risk is already becoming reality. The best insurance against open access fees compromising quality control at journals would be to make the quality control process itself transparent. Increased transparency in the publishing process is a recurring theme in this perspective and will reappear as a proposed solution to challenges with the current journal-based publishing process, which we describe next.

Impact factor and the academic incentive system: the good, the bad, and the ugly

Scientific articles are a major intellectual output of the research enterprise and an important basis for evaluating the productivity and impact of individual scientists. Expert evaluation is and will remain the gold standard for judging scientists and their output. However, we recognize that additional indicators of research quality and impact are necessary and useful; a shorthand gauge of quality helps scientists and nonscientists alike to identify high-quality scientific work amid the vast sea of published manuscripts. At the moment, the journal name is used as such an indicator of quality: the assumption is that articles are of high quality and impact if they are published in journals that are perceived as prestigious. Journal editors set standards for their journals and choose what to publish accordingly. Journals like Cell, Science, and Nature, which are considered the most prestigious journals in the life sciences, aim to publish the most highly citable articles in each field, since the number of citations of an article is a measure of its influence. The journal metric that is most widely used to signal this prestige is the journal impact factor – the average of citations in a given year garnered by all articles published in the journal over the two previous years. The impact factor has become such a predominant metric because it discriminates well among journals. Journals like Cell, Science, and Nature publish, on average, more highly cited papers and thus have a higher impact factor. But like any metric that relies on the mean, this one is easily skewed by outliers, such as heavily cited papers. The distribution of article citations actually overlaps significantly between journals that have markedly different impact factors (Lariviere et al., bioRxiv, 2016; Kravits and Baker, 2011). A glass-half-full perspective emphasizes that editors of journals with a high impact factor manage to attract – at least on average – articles that end up being more highly cited; a glass-half-empty perspective highlights that they certainly don’t do it consistently.

Why do all journals publish articles of varying influence? There are three reasons. First, citation rates differ significantly among fields, with the number of scientists in a field and its translational potential typically increasing citation rates. Second, the opinions of the chosen two to four peer reviewers for a given paper may, by chance, not be representative and thus may lead to an erroneous publishing decision. Third, nobody – not even experts or editors – has a crystal ball to accurately predict at the time of an article’s publication what its eventual impact will be. In the end, only time, replication, and extension of the research data can truly validate experimental findings and conclusions and determine their long-term impact. These inherent limitations explain why scientific journals will always publish papers that vary in influence, despite efforts by their editors to try to ensure consistency.

The variability in the influence of the articles in a given journal does not cause damage per se. The damage comes from an academic incentive system that equates the journal name, specifically the corollary metric of the journal impact factor, with a given paper’s quality and impact – in effect devaluing those papers in lower-impact-factor journals that are actually of high impact and overvaluing papers of low quality or impact in journals with a high impact factor. Journals promote their impact factor, and many academic institutions and funders are, unfortunately, complicit in using it for hiring and funding decisions. The combination of long term growth of the biomedical research enterprise and recent stagnation in federal funding has fueled hyper-competition for research funding, jobs, and publication in high-impact-factor journals and has rendered the impact factor an even more corrosive indicator of research quality and impact. It is particularly alarming that the next generation of scientists perceives a need to publish in Cell, Science, and Nature to be competitive for faculty positions. Evaluating scientists based on where they publish, rather than what they publish, weakens important elements of the biomedical research enterprise, including integrity, collaboration, and acceleration of progress. It shapes the behavior of scientists in undesirable ways, tempting them to exaggerate their work’s impact, to choose research topics that are deemed suitable for top journals, and to refrain from open sharing of data and other research outputs.

Integration of peer review with the publishing decision: thumbs-up sums it up

Why does the academic incentive system rely on journal-based metrics like the impact factor when those metrics are inherently limited in their ability to evaluate the contributions of individual scientists? One major reason is the very structure of the publishing process, in particular the nontransparent integration of peer review with the publishing decision. Most journals keep peer reviews a confidential exchange among editors, reviewers, and authors, which gives editors flexibility to use their own judgment in deciding what to publish. It leaves their decision to publish as the only visible outcome of the evaluation process and hence the journal name and its impact factor as the only evident indicators of quality. In addition to encouraging the widespread use of impact factor in the evaluation of scientists, the tight and nontransparent linkage between peer review and the editorial decision contributes to other serious problems in publishing:

- The main purpose of peer review should be to provide feedback to authors in order to improve a manuscript before publication. But, in service of the publishing decision, peer review has morphed into a means of assisting editors in deciding whether a paper is suitable for their journal. Scientists may disagree on technical issues, but at least they can “agree to disagree” and keep the technical discourse constructive. Assessing whether a paper is “novel enough” or “above the bar” for a journal tends to be the most acrimonious and frustrating aspect of the peer review process because it is more subjective. It is important to identify papers with broad impact, and peer reviewers can contribute to that appraisal by properly describing the scientific context of the work in question. But the work’s suitability for a given journal should not be a concern for peer reviewers.

- The intense competition for publication in high impact factor journals likely increases how often and to what extend scientific articles are revised before publication. While most papers are significantly improved through revisions suggested by reviewers and editors, there is a sense among scientists that a significant fraction of the time spent on revisions, resubmissions and re-reviews is not adding sufficient value and needlessly delays the sharing of findings.

- Important long-term evaluations of scientific work are not captured if the major quality controls conclude with the publishing decision. Experts know which papers in their field have stood the test of time. But for non-experts, it is more difficult to discern which high-profile papers have been built upon and which turned out to be dead ends. Longer-term evaluation is critical today for other reasons: the shift from data generation to data analysis as the rate-limiting step in research, and the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of research, pose challenges for even the best peer reviewers (Kaelin, Nature, 2017). How can we expect peer reviewers to verify the accuracy of all data and conclusions when this job could take a significant fraction of the time it took the authors to produce their analysis in the first place? While future technological solutions may considerably speed up the reanalysis of research data (see https://mybinder.org/ for an example of such a solution), it is time to acknowledge that peer review before publication is just the initial step in scientific evaluation.

In summary, the current journal-based publishing system drives the use of the impact factor in the evaluation of scientists, it renders the peer review process more adversarial than it needs to be, it delays dissemination of research findings, and it fails to capture the long-term impact of scientific articles.

Recommendations

We propose three changes to address the shortcomings described in the previous sections. While these changes could be implemented independently, together they promise to significantly increase transparency and efficiency in scientific publishing:

- Improve the peer review process

- Put dissemination of scientific articles in the hands of authors

- Develop a system of post-publication article evaluation

Improve the peer review process

Make peer review transparent: Currently, the publishing decision itself is the quality proxy for scientific articles. Publishing the peer review reports on a manuscript, anonymously or with attribution, would change that. Scientists would be able to take into account the peer reviews, not just the editor’s decision, when they evaluate the work of another researcher. As pointed out above, transparent peer review could also address the serious risk that open access publications become paid advertisements.

Ensure higher-quality peer reviews: Publishing peer reviews would likely motivate peer reviewers to more consistently execute their role well. Two other measures would further improve the quality of peer reviews. First, consultations among peer reviewers – a practice pioneered by journals such as the EMBO Journal and eLife – could effectively eliminate unreasonable reviewer demands. (It is also an ideal vehicle to introduce early-career scientists to the art of peer reviewing – what better way to learn than by consulting with a seasoned peer reviewer?) Second, peer reviews should focus on the technical quality and scientific background of the submitted work. The goals are to evaluate whether the conclusions of the article are warranted and to provide context that can serve as a scientific foundation for any subsequent evaluation of a paper’s broader impact, by either an editor or a reader. By sidestepping the suitability of the work for a particular journal, peer review would become more constructive and, in principle, transferrable among journals.

Give recognition for peer review: We recognize that many scientists are concerned that peer reviewers would not be as forthcoming with their critiques if signing reviews becomes compulsory. However, we hope that over time, reviewers will increasingly opt to sign their reviews. Signing of peer reviews aligns better with the notion that peer review is a scholarly activity that deserves credit. Considering that peer review is such a labor-intensive activity and a cornerstone of the scientific enterprise, we need to devise better ways to recognize scientists who contribute outstanding peer review services to the scientific community. Peer reviews should be given their own DOI, as they already are by some journals with open peer review practices and by Publons (Lin, Crossref blog, 2017), making it possible to cite peer reviews and include them on the peer reviewer’s CV or ORCID profile. Widespread signing of peer reviews would also enable a community-wide analysis of peer review patterns, informing future suggestions for peer review improvements.

Put dissemination of scientific articles in the hands of authors

Funders entrust scientists with the execution of research. This trust in the creativity and independent judgment of individual scientists or groups of scientists is at the heart of the research enterprise. The research article is a major output, and often the culmination, of this research. Curiously, the trust in the researcher breaks down at the point of dissemination, since we have transferred the decision to publish to editors. Why do we trust scientists in the design and the execution of their research yet insist that editors should decide when this research is ready to be published? Or, to look at the flip side, if we feel so strongly that an independent party like an editor should make the publishing decision, why don’t we ask independent parties to oversee experimental design and execution as well? If we agree to trust scientists to do research, then we should also trust them to decide when to publish that research.

Making authors the publishers of their own work has additional benefits. For starters, it solves the problem that we identified at the outset: that the journal’s publishing decision is used as an indicator of quality. Since authors have such a clear self-interest in publishing their own work, nobody would equate the author’s decision to publish with a stamp of quality. This stamp of quality has to come from elsewhere, including the published peer reviews and post-publication evaluations described below. In addition, the peer reviewers would direct their comments to the authors focusing their peer reviews on improving the manuscript as opposed to advising the editor on suitability for a journal. The overall publishing experience for authors would improve significantly, since they would publish when they considered the work to be ready. The time and resource savings would be significant: authors wouldn’t have to perform experiments that they deem unnecessary; consecutive submission and evaluation at several journals would decrease; and the time-to-publish interval, which keeps increasing due to demanding revisions and multiple rounds of review, would decline, since authors would control publication.

A major concern with this model is that an author is not as impartial as an editor. The best insurance against authors’ poor decision-making is the link between their published work and their reputation. Few authors will knowingly want to put out poor-quality work. Sometimes authors may want to rush publication of a competitive story, but preprint servers can now disseminate papers so much faster that there may be less pressure to rush publication after peer review. The peer reviews themselves will be a powerful restraint on the author, since they will be published together with the paper (see above). An author may, for example, prefer to withdraw a paper submitted to a journal if the reviews reveal fundamental flaws that cannot be addressed with revisions. And if an author decides to publish a paper despite serious criticism from reviewers, at least those criticisms will be accessible to readers, who can decide for themselves whether to side with the author’s or the reviewers’ point of view. This is arguably better than the situation today, in which authors can publish any work somewhere (though not necessarily in the journal of their choice), typically without critical reviews that might highlight potential shortcomings.

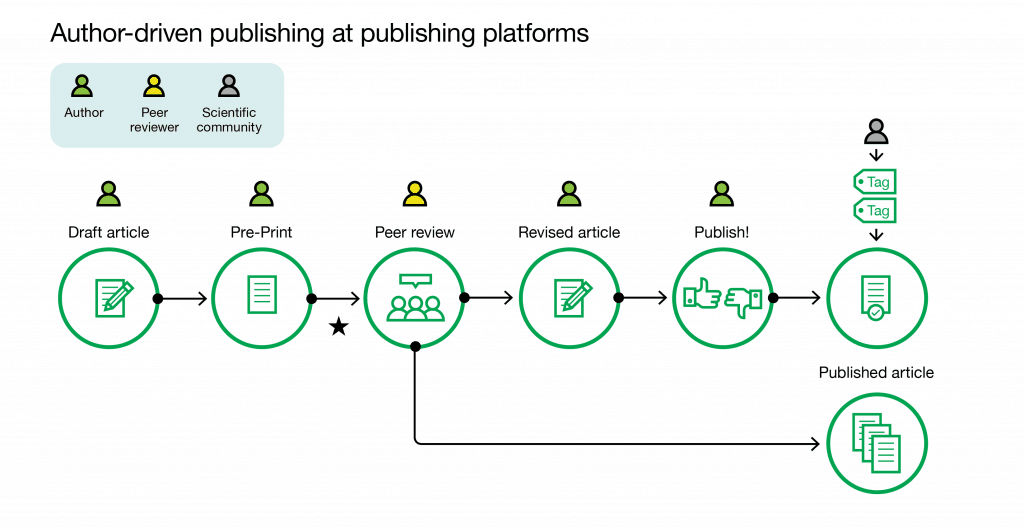

Author-driven publishing is already practiced at preprint servers and publishing platforms such as F1000Research. The difference between a publishing platform and a journal is that the author replaces the editor in all major gatekeeper roles (Fig. 1C): the submitted article is immediately published as a preprint; the author-selected peer reviewers evaluate the work; the attributed peer reviews are published together with the revised manuscript when the author decides to publish; and version control allows the author to update the manuscript (Tracz, F1000Research, 2016). All versions and all peer reviews are available under an open access license. Such articles are also indexed in PubMed, the National Institutes of Health’s searchable database of life science research articles, if at least two reviewers have signed off that the work is technically sound. Several funders, including the Wellcome Trust and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, have established open research platforms based on the F1000Research model. Future experiments with publishing platform models may differ in important ways – such as how they select articles for peer review (will every submission be reviewed?) and how they select peer reviewers (should the author or an independent entity select reviewers or should peer reviewers self-select?). Publishing platforms, where authors replace editors as gatekeepers, are an exciting model for scientific publishing in the future because they provide an efficient and fully transparent completion of the research workflow and best satisfy requirements for the open sharing of research outputs.

Where does this leave journals and editors? We envision that journals can transition toward a publishing platform without giving up all editorial gatekeeper roles at once. For example, journal editors could retain the first editorial gatekeeper function of selecting articles for journal-orchestrated peer review (editorial triage), but relinquish the publishing decision to authors on the condition that the peer reviews and any author responses will be published as well (Fig. 1B). Journals would basically commit to the publication of all peer reviewed articles. In rare cases, editors may need to step in and stop publication of an article when the peer review process reveals that publication would be inappropriate – for example, in cases of plagiarism, data fabrication, violation of the law, or reliance on nonscientific methods.

The editorial triage step serves the purpose of allocating peer review resources wisely. Rigorous peer review is time-consuming and particularly important for scientific articles that could have a broad impact, because validation from experts allows scientists from other fields to build on the data and conclusions. More specialized research articles may not need the same level of peer review, since they are mostly read by experts who can evaluate the work themselves. Editorial triage at prestigious journals is the traditional method that ensures that reviewer resources are used only for scientific work that is of sufficiently broad interest. Directing peer reviewer resources to broad-interest articles that need them most is currently not addressed at publishing platforms where all papers are reviewed equally. It may be possible over the long term to replace this editorial gatekeeper role if it becomes feasible and culturally acceptable to use community approaches to select works of broad impact for detailed review. At that point, the journal would transition to a full-fledged publishing platform.

We believe that academic publishers like scientific societies are ideally placed to experiment with this transition from journal to publishing platform. Typically run by practicing scientists, these journals may have a natural affinity for the concept that authors should bear more responsibility and rights for what and when they publish. But equally important, a transition to author-determined publishing offers these journals a path to financial sustainability in an open access context. At the moment, society journals are between a rock and a hard place. They can’t afford to switch to open access, since the open access fees required to replace their subscription income would be too high for readers. On the other hand, they feel considerable pressure from for-profit publishers who are launching competing journals at breakneck speed. Academic publishers risk becoming obsolete if they don’t adjust. The proposed author-driven publishing model provides such an opportunity. A journal’s commitment to publish all peer reviewed articles immediately increases the number of published papers and opens the door to charge for peer review instead of for publication. The journal would thus receive income on a larger share of the manuscripts it handles, reducing per-article open access fees.

Publishing platforms and journals where authors decide when to publish explicitly forgo the editorial selection that currently occurs after peer review – and, with it, the (limited) ability to enforce a quality standard. Journals and editors can then focus on curating published articles through post-publication evaluation, which we discuss next.

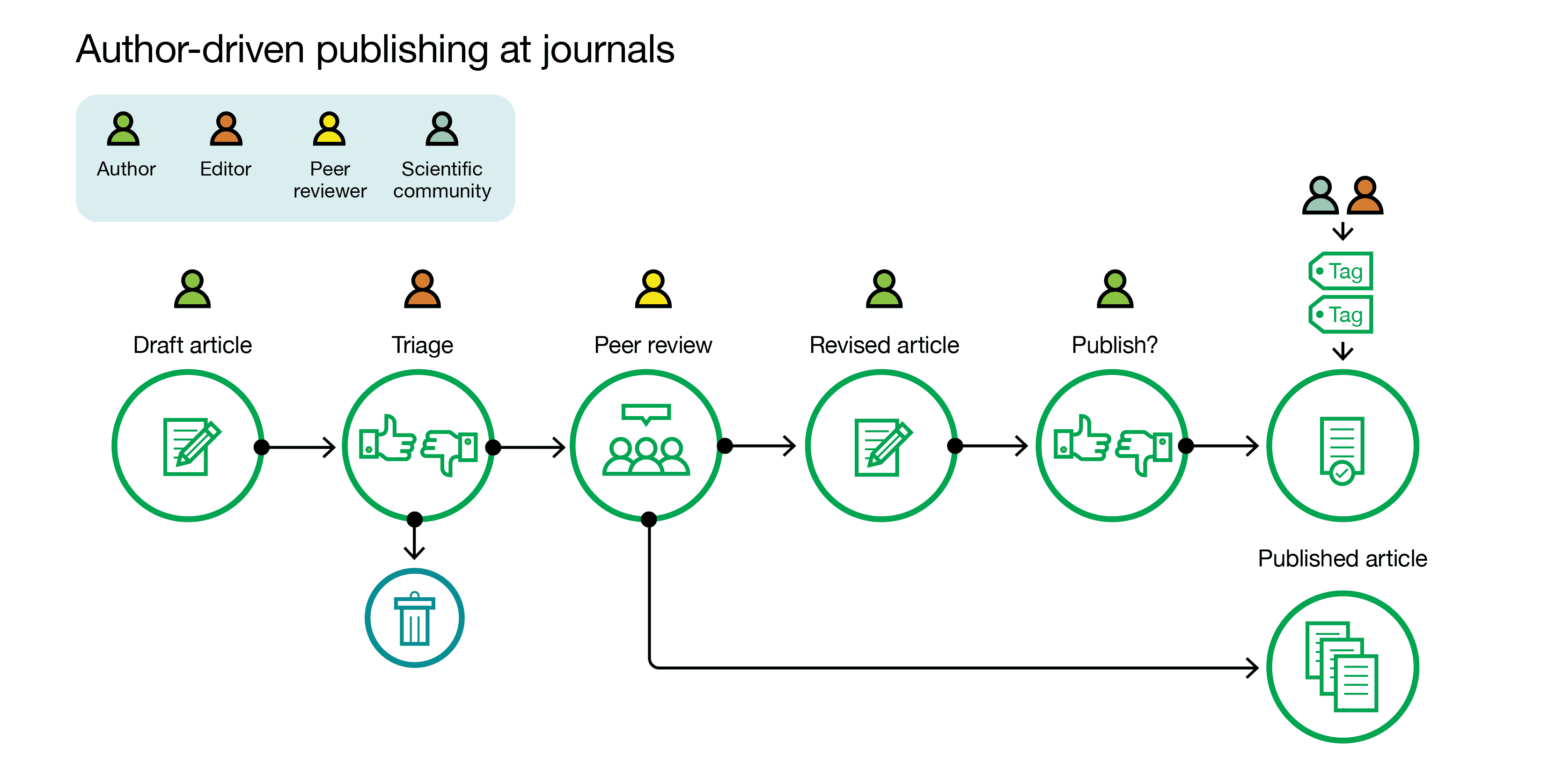

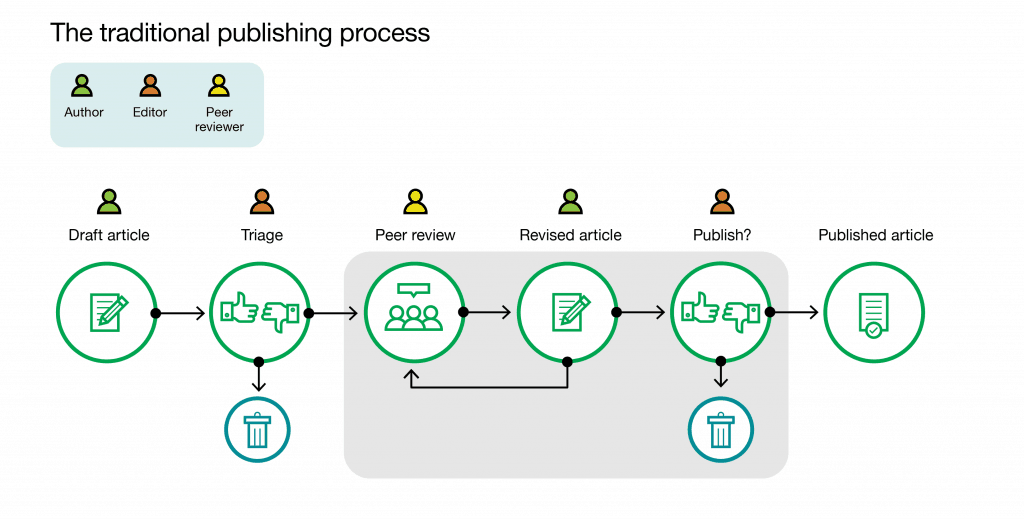

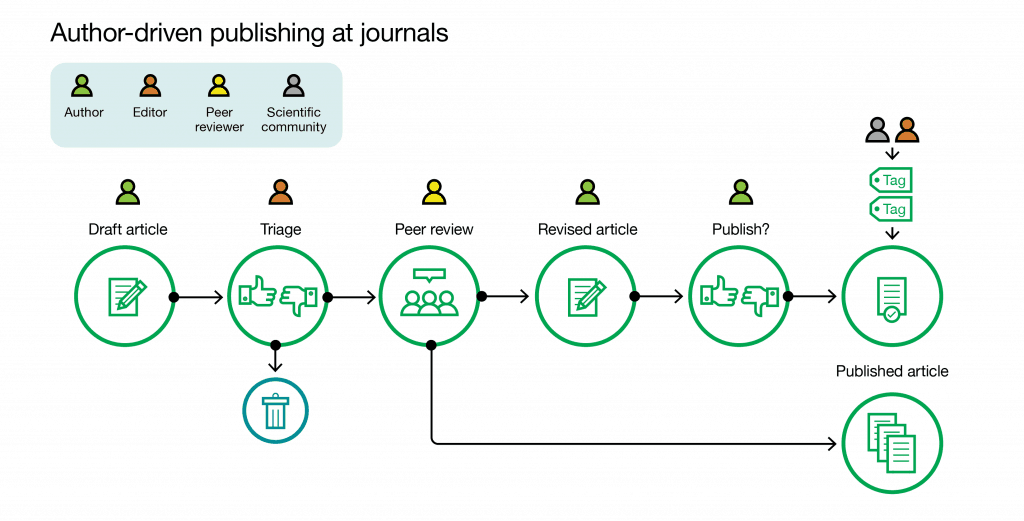

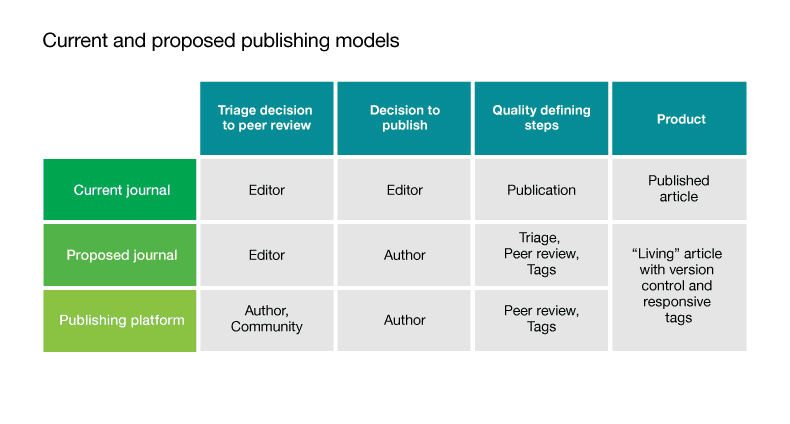

Fig. 1 Current and proposed publishing models for the life sciences

A.The traditional publishing process. Editors fulfill two critical gatekeeper functions: editorial triage and the decision to publish. The box (“black box”) signifies that the step between peer review and the publishing decision is typically confidential, making the published article the only visible outcome of the processes in this box. B. Author-driven publishing at journals. Editors still conduct editorial triage, but authors decide what and when to publish. The peer reviews are published together with the article. Tags are added by editors and other scientists to facilitate post-publication evaluation. C. Author-driven publishing on publishing platforms. The star indicates that peer reviewers can be selected in various ways: by authors, by self-selecting reviewers, or by yet-to-be-determined community approaches. As in B, peer reviews are published and tags evaluate articles post-publication. Editors are not listed for C, since they do not fulfill any gatekeeper roles, but they can contribute to post-publication evaluation.

Develop a system of post-publication article evaluation

The current publishing system is particularly ill-suited to adopt post-publication evaluation for articles, since the major quality control steps conclude at the time of publication. With the life sciences becoming increasingly interdisciplinary and data-rich, it is critical to supplement published peer review reports with post-publication measures of validation. These measures, which we refer to as “tags,” could capture, in shorthand, a particular aspect of a paper – such as its technical quality, intellectual rigor, or breadth of interest. A precedent for tags exists in the F1000Prime service, in which experts identify articles they consider of most interest to their field – in effect “tagging” these articles. Similarly, badges to acknowledge open practices have been attached to articles at the journal Psychological Sciences, where they may contribute to an increase in data sharing (Kidwell et al., PLOS Biol, 2016).

In post-publication evaluation, we envision that tags could be created by journal editors, perhaps initially to reflect aggregated reviewer scores. Tags have the capacity to extend the validation process well beyond the initial peer reviews and to capture article-specific indicators, both quantitative and qualitative, that reflect an article’s value to the scientific community over longer time periods. Tags can come in many flavors, taking full advantage of internet capabilities through crowdsourcing and analytics, while still preserving the critical input from professional and academic editors as adjudicators of quality. Some tags could be created automatically and standardized across journals. For example, tags could capture the long-term impact of a paper through a metric like relative citation ratio – an article-specific metric recently developed at the National Institutes of Health (Hutchins et al., PLOS Biol, 2016). Other tags could reflect data downloads and reuse. Tags could also be useful in tracking the reproducibility of a published study: scientists who were successful (or unsuccessful) in reproducing or building upon the study could contribute to a crowdsourced reproducibility tag and link to their follow-up study. We should, of course, be mindful that tags, like any proxy, could be manipulated. But at least tags would be superior to journal-based metrics like the impact factor, since they would be article-specific and could change over time to reflect the changing impact of a paper to the scientific community.

Tags take on particular significance in the proposed author-driven dissemination model. If authors decide when to publish, we lose the impartial voice of editors in the publishing decision. This editorial role can be executed through tags. For example, if authors decided to publish an article against reviewers’ recommendations, the editors wouldn’t stop publication but could attach a “red flag” tag that highlights the controversial nature of the paper and encourages readers to take a closer look at the published peer reviews. Today, editorial opinions factor into the publishing decision in important but opaque ways. “Editor’s choice” tags could capture these opinions and might differ from peer reviewer scores. Importantly, we could evaluate the predictive power of all these tags – over time, identifying those scientists with a particularly good nose for high-impact work. We feel that the tag system is an exciting new approach that could capture the important role that editors play in curating the scientific literature. Unlike the primary research that we believe should be disseminated in an open access format, we think some curation services could be subscription-based and conducted by commercial and academic publishers alike.

Tags could stratify published papers within a journal and help readers gauge the quality of articles. In contrast to the offerings of traditional publishers, who have created families of journals that cascade from high to low selectivity, tags could create, in effect, a quality cascade within a journal, sorting papers according to particular quality tags. We think that this type of internal cascade could be a much more efficient and effective way to differentiate published papers than the current journal system; a paper would typically have to be reviewed just once and would then rise or sink in importance based on its post-publication tags. A re-review may occasionally be in order to replace unreasonable reviews, but the existence of long-term impact tags could vindicate a paper, even if it erroneously received overly negative tags immediately after publication.

The shift to author-driven publication and the introduction of post-publication tags would change the rules of the game, since the act of publication would no longer be a quality-defining step. If these tags prevail as indicators of scientific quality, scientists will care about them and will no longer see a need to publish papers in extremely selective journals. Tomorrow’s scientists will not associate quality with a particular journal name but with the peer reviews and the tags that are attached to a paper (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Summary of current and proposed publishing models

Future outlook

The notion that high-impact-factor journals are synonymous with importance is deeply engrained in the scientific community. Focusing editors on their critical role as curators and restricting their role in the publishing decision will therefore be a significant cultural shift. But this shift makes sense: why should the act of publishing still be the main quality-control mechanism in sharing science when publishing itself is cheaper, faster, and easier than ever before? Instead, publishing in the digital age would benefit from more robust and transparent pre- and post-publication evaluations; a transparent peer review process that is recognized and rewarded as a critical scholarly activity and that focuses on improving scientific articles before publication, not on its suitability for a particular journal, and we need article-specific quality measures that extend beyond the time of publication. These changes would shift publishing and the academic incentive system away from journal-based to article-based metrics that better reflect the true contributions of scientists. The benefits would include a more transparent and efficient publishing system, with robust yet evolvable post-publication evaluation. We believe these changes could put science, and scientists, back at the heart of scientific publishing.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kathryn Brown, David Clapham, Gerry Rubin, Sean Carroll, Heidi Henning, Boyana Konforti, Judy Glaven, Janet Shaw, Viknesh Sivanathan (all from HHMI), Mark Patterson (eLife), Robert Kiley (Wellcome), and Jessica Polka and Ron Vale (ASAPbio) for feedback on drafts of this manuscript.

References

Ian Hutchins, Xin Yuan, James M. Anderson, George M. Santangelo, “Relative Citation Ratio (RCR): A New Metric That Uses Citation Rates to Measure Influence at the Article Level,” PLoS Biol 2016 Sep 6;14(9):e1002541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002541.

William G. Kaelin Jr., “Publish houses of brick, not mansions of straw,” Nature 545, 387 (23 May 2017), doi:10.1038/545387a.

Dwight J. Kravitz and Chris I. Baker, Front Comput Neurosci, 2011, https://doi.org/10.3389/fncom.2011.00055. “Toward a new model of scientific publishing: discussion and a proposal”

Mallory C. Kidwell, Ljiljana B. Lazarević, Erica Baranski, Tom E. Hardwicke, Sarah Piechowski, Lina-Sophia Falkenberg, Curtis Kennett, Agnieszka Slowik, Carina Sonnleitner, Chelsey Hess-Holden, Timothy M. Errington, Susann Fiedler, Brian A. Nosek, “Badges to Acknowledge Open Practices: A Simple, Low-Cost, Effective Method for Increasing Transparency.” PLoS Biol 14(5): 2016 e1002456. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002456

Jennifer Lin, https://www.crossref.org/blog/peer-reviews-are-open-for-registering-at-crossref/ 2017

Vincent Lariviere, Veronique Kiermer, Catriona J. MacCallum, Marcia McNutt, Mark Patterson, Bernd Pulverer, Sowmya Swaminathan, Stuart Taylor, Stephen Curry, “A simple proposal for the publication of journal citation distributions,” bioRxiv, Sept 11 2016, doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/062109.

Vitek Tracz, Rebecca Lawrence, “Towards an open science publishing platform.” F1000Res 2016 Feb 3;5:130. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7968.1.

This is a nice idea. But “tag” is the wrong word here. It is frequently used online in various existing ways that might be confused with this – e.g. in blogging – and of course tags also refer to the basis for article mark up. A much better word would be “badge.

thanks Richard. You raise a good point. We’ll consider changing the term to badges.

I definitely think C would be the best way to go. Science should be back to the hand of scientists. But one should expect publishers to fight back to preserve their huge income sources…

HI Olivier,

thanks for your comment. You are right that model C will not be palatable to publishers who favor the status quo. But if the scientific community agrees that model C is the best solution for science, we can move towards it through experiments outside the journal system or in collaboration with journals that are willing to change.

The publishing system you want to develop is extremely interesting. Just one thing that we do not clearly understand: When an author deposits his/her preprint in an open archive, he/she publishes (makes publicly available) his/her article. So, is there a fundamental difference between the deposit of a preprint on an open archive and the publication by the author? Fig C suggests a difference since the ‘pre-print’ and ‘publish’ steps are disconnected. Right?

The system you describe seems close to a system that we have been proposing for a year (with some differences): Peer Community In (PCI). The first community – Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology (PCI Evol Biol, evolbiol.peercommunityin.org) – has already evaluated preprints and published recommendations for preprints. Two other PCIs just come out: PCI Paleontology (paleo.peercommunityin.org) and PCI Ecology (ecology.peercommunityin.org.

This system is based on the existence of disciplinary communities that evaluate on the basis of peer review and possibly recommend preprints deposited on open archives. The system is extremely inexpensive and therefore can be offered free of charge for readers and authors (thanks to a few small public subsidies).

A description of this system can be found here: https://peercommunityin.org and a short video can be seen here: https://youtu.be/4PZhpnc8wwo

The similarities with your proposal are striking:

-‘First, publish peer reviews, whether anonymously or with attribution, to make the publishing process more transparent.’

–> In PCI, peer reviewers are chosen by 1 ‘recommender’ of the community (similar to an editor of a journal). If the preprint is eventually ‘recommended’, peer-reviews (signed or not), authors replies, and recommendation (signed) are published (freely)

-‘Second, transfer the publishing decision from the editor to the author, removing the notion that publication itself is a quality-defining step.’

–> In PCI, we do that if preprint deposit on preprint open archives is considered a publication.

-‘And third, attach robust post-publication evaluations to papers to create proxies for quality that are article-specific, that capture long-term impact, and that are more meaningful than current journal-based metrics’

–> in PCI we publish a recommendation of the peer-reviewed preprint when peer-reviews are positive, convergent and the preprint is considered recommendable by one of the community member.

The main difference with what you propose is that peer-reviews are not published if the preprint is not recommended by the ‘recommender’ of the community. However, reviews are sent to the author to allow him/her to improve his/her manuscript.

Thanks for the thoughtful ideas!

The publishing system you want to develop is extremely interesting. Just one thing that we do not clearly understand: When an author deposits his/her preprint in an open archive, he/she publishes (makes publicly available) his/her article. So, is there a fundamental difference between the deposit of a preprint on an open archive and the publication by the author? Fig C suggests a difference since the ‘pre-print’ and ‘publish’ steps are disconnected. Right?

The system you describe seems close to a system that we have been proposing for a year (with some differences): Peer Community In (PCI). The first community – Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology (PCI Evol Biol, evolbiol.peercommunityin.org) – has already evaluated preprints and published recommendations for preprints. Two other PCIs just come out: PCI Paleontology (paleo.peercommunityin.org) and PCI Ecology (ecology.peercommunityin.org.

This system is based on the existence of disciplinary communities that evaluate on the basis of peer review and possibly recommend preprints deposited on open archives. The system is extremely inexpensive and therefore can be offered free of charge for readers and authors (thanks to a few small public subsidies).

The similarities with your proposal are striking:

-‘First, publish peer reviews, whether anonymously or with attribution, to make the publishing process more transparent.’

–> In PCI, peer reviewers are chosen by 1 ‘recommender’ of the community (similar to an editor of a journal). If the preprint is eventually ‘recommended’, peer-reviews (signed or not), authors replies, and recommendation (signed) are published (freely)

-‘Second, transfer the publishing decision from the editor to the author, removing the notion that publication itself is a quality-defining step.’

–> In PCI, we do that if preprint deposit on preprint open archives is considered a publication.

-‘And third, attach robust post-publication evaluations to papers to create proxies for quality that are article-specific, that capture long-term impact, and that are more meaningful than current journal-based metrics’

–> in PCI we publish a recommendation of the peer-reviewed preprint when peer-reviews are positive, convergent and the preprint is considered recommendable by one of the community member.

The main difference with what you propose is that peer-reviews are not published if the preprint is not recommended by the ‘recommender’ of the community. However, reviews are sent to the author to allow him/her to improve his/her manuscript.

Thanks for the thoughtful ideas!